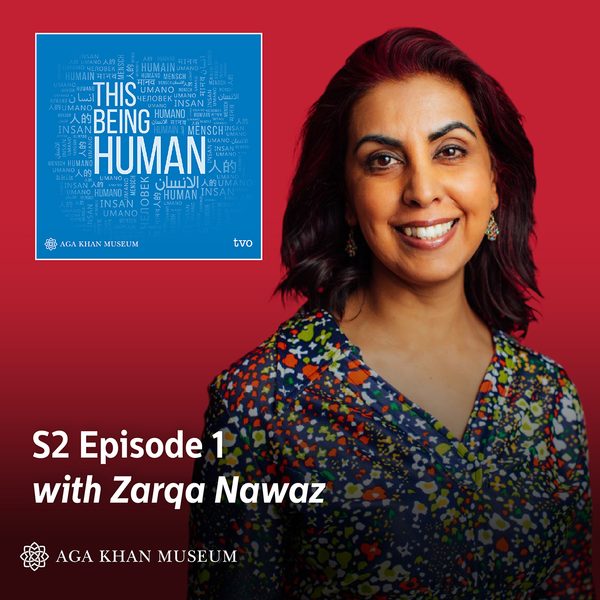

This Being Human - Zarqa Nawaz

Zarqa Nawaz is going through a bit of a rebirth. It’s been roughly a decade since the end of her hit show Little Mosque on the Prairie. Recently, Zarqa got into stand-up comedy, she’s about to star in the web series ZARQA, and she is on the verge of releasing her first novel, Jameela Green Ruins Everything, a dark comedy about American intervention in the Middle East. Zarqa talks about using comedy to address uncomfortable or taboo topics, from dating and divorce in Muslim culture, to the rise of ISIS. She also discusses how she has dealt with backlash from her community and what it’s like to step out from behind the camera.

The Museum wishes to thank Nadir and Shabin Mohamed for their founding support of This Being Human. This Being is Human proudly presented in partnership with TVO.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK VOICEOVER:

Today, the big talent behind the Little Mosque.

ZARQA NAWAZ:

You know, we live in a secular world and things that are religious and things that emanate God consciousness are not really welcome. And I want to break that ceiling, that sort of glass ceiling of faithfulness.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK VOICEOVER:

Little Mosque on the Prairie was not only one of the most successful Canadian TV shows in recent history – it also changed the way Muslims are portrayed in pop culture. For six seasons, the award-winning series brought a small Saskatchewan mosque to millions of viewers around the world. It was groundbreaking. In a post 9-11 world, the show portrayed Muslim life with humour and nuance. And it was life-changing for its creator, Zarqa Nawaz. She could have kept at it. She could have made a spinoff, or a new network show. But instead, she’s in the midst of a series of creative reinventions. This spring she’ll release her debut novel, Jameela Green Ruins Everything, a satire about foreign policy in the Middle East that pokes fun at ISIS. She’s also releasing a web series called Zarqa about a divorced Muslim woman re-entering the dating world, which she’ll star in herself. AND she’s recently started doing standup comedy. The thread that binds all of these projects together is her own particular take on Muslim culture —especially the uncomfortable parts. Sexuality, government surveillance, no-fly lists are often finding a way into her humour. And while the jokes in Little Mosque may seem tame today, she faced a lot of backlash at the time. In fact, some people wanted to throw her out of her own little mosque on the prairie. None of the controversy is surprising to me. I grew up around Zarqa. As kids, we went to the same mosque in Toronto before she relocated to Saskatchewan and launched the show that changed everything. We caught up recently to talk about humour, faith, and diving into the unknown.

ZARQA NAWAZ: I’m so glad to be here.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK: Zarqa, I have to share a memory with you. We grew up in the same Muslim community in Toronto together. I just remember as long as I was sort of aware of what the aunties were talking about, that Zarqa Nawaz was this controversial character amongst the elder brothers and sisters in the community, you know, when the aunties would talk about you, it was like “That Zarqa Nawaz is so precocious. That Zarqa Nawaz is so outspoken. That Zarqa Nawaz speaks back to her parents and her elders. That Zarqa Nawaz is so forthright.” I have this memory of you being this sort of young person who was always pushing, pushing the envelope of cultural acceptability and certainly annoying some of the aunties in the process. Are you still that Zarqa Nawaz?

ZARQA NAWAZ:

You know, it’s so interesting that you tell me that because I don’t think I was aware of that at all. And I think that’s one of the reasons I get myself into so much trouble is that I’m walking around with these like blinders on and really thinking, oh, everyone loves me. Everyone loves what I’m doing! And then when the backlash happens, I’m like, what happened? Why does no one love me? And I’m like, what’s wrong with me? Why am I not understanding the backlash at all? Because I think I literally don’t get it. I don’t think it really hit me until after Little Mosque on the Prairie aired, and the Muslim community was so upset with me and I was like, but why? All — the whole time growing up, you sent us to camps and conferences and told us that it was important to get in media and to represent. And I’m finally representing, and you guys are so mad, and I don’t think I really understood that my cultural upbringing as a Canadian, I was born in Liverpool, U.K., raised in Canada, and my sensibility was very different than, say, the sensibility of my parents’ friends and of that generation. And there was this inherent disconnect, and I didn’t recognize that. I did not see it. I didn’t realize it until it was too late, until Little Mosque aired and then the backlash started, and I was just like, I don’t understand what I did wrong. I thought you guys would be so happy. And that’s when it started to dawn on me that, you know, comedy is not that translatable to different generations and to different cultures, and that what I thought was funny, even though I was making jokes about the Muslim community, it was getting lost in translation and people were feeling like I was making fun of the divine. I was making fun of God. I was making fun of the faith and that they were the representatives of the faith. And thus, I had to be schooled and that, and they were trying to school me and I was trying to explain to them and there, you know, and never the twain will meet. And ultimately, what saved me, I think, was that non-Muslims were watching the show and they were talking to their Muslim friends and they were saying, we love this. It helps us connect with your community and with Islam. And then we realized that this community is just the same as every other community. And when Muslims realized nothing catastrophic was really happening, in fact the opposite was happening — and it took a good year, maybe possibly two years of the show being out and Muslims to feel comfortable and realize that I had actually not destroyed the reputation of the faith. The people calmed down because it was a really painful time for me. You know, like my husband was the president of the mosque. He had to, you know, people were telling him he had to divorce me. I couldn’t go to the mosque anymore. There was a petition filed against me. I had to withdraw my membership, I couldn’t- I just couldn’t understand what was happening. I mean, this was the community I grew up in, I belonged to. These were my people, and it was this out and out rejection. And it took a long time of soul searching to understand that if you’re going to be the first person, and I didn’t even know I was the first person, that was how innocent I was, that if you’re going to be the first person to go out and create comedy in the mainstream, you’re dealing with a community that, you know, is already suspicious. They’ve had to deal with so much trauma from, you know, being misrepresented for centuries, that there’s a higher level of sensitivity. And I had to understand that.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Whatever it was, the show really broke through. How did that feel for you as the creator of the show? You know, we got this big political backdrop. You’re dealing with your own experiences with Muslim communities, these incredibly sensitive issues that the show addresses and then it’s an unmitigated hit.

ZARQA NAWAZ:

You know, I felt I had to protect my Muslim community because I didn’t reveal any of the things I’m revealing today in 2021 because I feel like we’re far enough removed where we can look back at it in perspective. But at the time, I didn’t want the media to know how I was being treated, how the community was reacting. So, I was just like, they love it. They’re so happy, they’re so supportive. Everything’s great, right? It’s just better that they don’t know because they’re not going to understand what’s happening, because I didn’t really understand what was happening, either. I didn’t want us to be lumped in with, “Oh those Muslims. They just don’t get comedy.” Because I had to understand and get perspective. And what I realized was that people react differently depending on the circumstances they’re in. For example, the Muslims in Europe versus the Muslims in Canada versus the Muslims in the U.S. because the American Muslim experience has been worse than the Canadian Muslim experience, particularly after 9/11. And so, they appreciated the show more, and I was getting calls to speak and talk to Muslim groups in the U.S., but not in Canada. So that was really fascinating to me, it was that you also have to take into consideration those experiences of post-9/11 and discrimination and oppression, which the American Muslim community experience in far higher degrees than the Canadian Muslim experience. I mean, it took a few years, but everything leveled off eventually. And then everyone came around and loved the show. And then other shows started like Citizen Khan in the U.K. and then Ramy. And then I noticed that in the comment section, people would go, oh, this isn’t as respectful as Little Mosque on the Prairie, which made me laugh, right? I was like, oh my God, you guys nearly took me out for that. And so, so when I when I remember sending a tweet to Ramy going, don’t worry about it, it’s going to be OK. The same thing happened to me because he was getting a lot of criticism. I go, you just gotta weather the storm. People react emotionally very quickly. And then, you know, gradually they get things in perspective, and you also learn from the criticism and adapt too. So, it’s a two-way street.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK VOICEOVER:

Zarqa may have adapted, but she hasn’t stopped pushing buttons. Her upcoming novel, Jameela Green Ruins Everything, is a dark comedy dealing with the rise of ISIS and American intervention in the Middle East. It follows the title character, a frustrated American writer, who tries to perform a good deed and accidentally gets caught up in a series of events that leads to becoming a spy in an extremist organization. Sounds harrowing. But believe me when I say it’s hilarious.

ZARQA NAWAZ:

It took me a long time to write the book, like I started in 2014 when ISIS first appeared and I was just like, you know, the vast majority of Muslims on Earth were like, “What is happening? This can’t be happening.” You know, because we worked so hard in terms of trying to get people to understand our faith as our community. And then all the headlines day after day after day. And it was just like, so exhausting. So, I started writing the book because I find writing and creating art is a wonderful way — it’s a therapeutic way of processing the world. So, I started writing a book about a Muslim woman who was very, you know, in a really bad place emotionally and mentally and was trying to sort out her life. And she gets caught up in this group. And through the book, I started doing the research of what were the – what were the political ramifications that caused this group to form? And I started doing a lot of research into the Afghan War in the 1970s and the first Gulf War and the second Gulf War, and so much information came in to me and I had to and I incorporated all in the novel and I had hired editors to help me write this book because it was such a difficult book to write, to write a satire about American foreign policy and to make it accessible to people. And they were like, “You’ve got to cut some of this stuff out and focus more on story and the human aspect because otherwise people will dial out and it’ll just be like a history lesson.” But I wanted it to be a history lesson. But it was this fine line about how do you tell a story where people get caught in the story and so compelled by the story, and then they just get little bits of history along the way that doesn’t derail them from getting sucked down into the story. Because I wanted it to be a learning process where you come out of it and go that was an amazing story. I loved it. But wow, those other things that I learned along the way taught me so much. It took a long time to sell because every editor was like, this is too crazy a story, like, I don’t know why, why are you writing this? This is too insane. Like a woman goes to the Middle East and gets involved in this terrorist group. And I remember I didn’t want to call them ISIS, so I called them the Dominion of the Islamic Caliphate and Kingdoms. And the original title was The Rise and Fall of DICK. And I thought, oh, isn’t this bri–

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

[laughs] I was in my mind. I was doing the acronym in my, in my head. I love it.

ZARQA NAWAZ:

Yeah, I loved it. My kids loved it. My family loved it. But the publisher did not love the acronym, and they’re like, no, no, this is like, this is crazy. Like, we got to change it. The wrong thing will come up if people Google that. And it was true. So, they changed it to Jameela Green Ruins Everything. And so, we made the sale. Finally, you know, I think it took like six or seven years of writing this book to finally make the sale. And I remember, you know, like, some Muslims kind of approach me and they’re like, “Oh, no, you can’t, you can’t go there, like Muslims and terrorism. And like, how could you write a story like, we were past this, you know, we don’t want to talk about this anymore.” And I knew right then and there, uh oh! I’ve done it again, like people are misunderstanding my intentions and why I wrote the book and what the purpose of the book is: that sometimes we’re going to have to talk about really difficult issues in order to put things in context of why they happened. And we can’t sort of run away from them or pretend it didn’t exist, even though it’s a painful thing to have to talk about. Because ultimately, the intention of the book is to talk about how these things impacted the Muslim world and, and how there’s never been talk of apologies or reparations for the people of Iraq for like this egregious, egregious harm that was caused to them. And I want to reignite those conversations.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Zarqa, you know, when you and I guess when you write a novel like this, you really, you really put yourself right, right in front of it. And, you know, we know that there’s a particular author telling the story. But you’ve also, it seems, done the same now because you’ve been doing standup. You started doing standup in 2020. That was brilliant timing, by the way. And you’re not only writing, but you’re starring in your in your own show. What does it feel like not being behind the scenes and being upfront? Being not just the writer, but actually being directly the messenger?

ZARQA NAWAZ:

It was hard! I didn’t actually want to do it. It was my producers, Liz and Claire, who was like, “No, you have to do it. That’s the standard trajectory of a standup.” I was expecting to do stand up for years like, you know, like Jerry Seinfeld and everyone loves Raymond. Like those guys had done it for years before they got their own show. And that was my intention. I thought, OK, I got Little Mosque on the Prairie. I kind of did it backwards where I got my show before I did the standup. And but I thought, okay, let’s go back and start from the beginning and understand comedy from its basics. And so, I started doing standup and I was doing okay for about six months until the pandemic shut it all down. And then there was no more opportunity, and I was like, “Oh no, like, what am I going to do?” And then this opportunity to shoot this trailer came up. And so, my friends, you know, Liz and Claire were like, “Well, you got to do it. Like you’ve started the standup, so it should be you doing it?” And I thought, OK, well, sooner or later, someone’s going to tell me, you’re not good enough. You shouldn’t be the star of this. So, I agreed to do the trailer and unfortunately did really well. [laughs] And then everyone was like, “Yeah, well, of course you’re going to be starring in the web series too.” And so then, the funding agencies were the only ones with any notion of what was happening. They were like, “You know, she should really go through intensive acting training because this is tough on anybody besides someone who’s never done it before.” So, I did like a year and a half of really intensive acting. And yeah, so I’m acting! [laughs]

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Tell us a little bit about this show because it’s pretty audacious.

ZARQA NAWAZ:

Yeah, I, you know, I got tired of shows where the Muslim woman is always like, you know, there’s like of all the experiences Muslims have in this world, like, we only get like the sliver, Muslim women get this tiny sliver of, you know, being the wife of the terrorist or being, you know, the mom who’s got a rebellious teen and she doesn’t understand them because they want to, you know, be liberated from this oppressive religion. Like, it’s always like the same slice of oppressed, quiet, shy Muslim woman. I’m like, enough already! You know, Muslim women have all sorts of experiences in this world and particularly of Muslim women who wear hijab, we’re always typecast as like the perfect good Muslim woman who would never make any mistakes. And of course, my community would very much like that to be true. [laughs] I thought no, Muslim women are flawed and, you know, if we believe in our faith that God wants us to make mistakes so we could ask for forgiveness, then let’s make those mistakes and show them to the world. So, I, you know, as you know, I have a reputation of being someone who is very impulsive and goes out and does things that upset people and I thought, wouldn’t it be hilarious – and by the way, this is not autobiographical. I’m not divorced, my husband would like everyone to know that – I wanted to play a Muslim woman who is divorced and finds out online that her husband is marrying a white yoga instructor half her age. You know, a trope. And she decides, instead of getting upset, she’s going to compete and bring her own white trope, which is a white brain surgeon named Brian. And she tells everyone she’s going to come with this white brain surgeon named Brian and she’s going to compete trope to trope. And so, she goes online and finds him. She finds a white brain surgeon who truly wants to have a relationship with her, doesn’t want to just become revenge, you know, arm candy. But the trouble is because she’s taken a photograph of him and told everyone she’s coming with him, he can blackmail her now to go on these sort of dates with him, which are very white centric, ya know, birding. And she’s like, oh no. This is comedy about how she goes through this, these dates and because of these dates, she kind of upends his life, upends her ex’s life. And kind of this is the way she rolls, right? She creates chaos wherever she goes with her impulsive decisions because she’s desperately trying to find a way to be happy and fulfill this need inside of her. And I feel that that is sort of, you know, as a as a child of immigrants, our parents inculcate us with this fear of failure because, you know, they have grown up with such trauma because of colonialism and displacement, particularly my parents who grew up in India, the partition in 1947, they became refugees. Had to come to Canada, start all over again. They inculcate us with this desperate need of success and fear of failure. And so, this is the character who has this fear of failure, and she’s always trying to become the best she can be at whatever she does in life and she’s constantly failing but creating chaos because of her decisions. And I kind of feel this is very autobiographical for me, right? I can never really satisfy myself but the bar keeps changing, right? There have to be, I have to have a more successful series, a more successful book. But as I try to do this, I cause chaos in my community and people are like, “What is she doing? What is she doing?”

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

There’s something so exciting. As you’re talking, I’m getting excited because I can’t wait to watch it. Why a web series, though? I would have thought that, you know, network would have picked it up or something else. Was there a particular reason behind doing it in this particular way?

ZARQA NAWAZ:

As a woman, I wanted to own my own television series and I wanted to understand the nuts and bolts of how television is made. For Little Mosque in the Prairie, I was on the creative side, but with the web series, CBC offers this really great opportunity, this funding out there that you can make a series and own it 100 percent and thus be aware of the whole nuts and bolts. Like, how does one contract writers, how does one contract actors, how does one make a budget, how does one deal with post-production? Who are all the people involved in making the series? And because it’s like a miniature television series, it’s small enough where one person can figure it all out and hire enough help around you. Like, I have fantastic producers Claire Ross Dunn and Liz Whitmere and figure out what does it take to actually make a series in a miniature level so that when you make it in a bigger level, you’re kind of aware of all the structural parts and components, and I wanted to know – it’s a machine. It’s like being a CEO of a company. And I really wanted to understand it. Because there are aspects of it that I want to do differently. I wanted to hire emerging directors, particularly in the First Nations community, because I live in Saskatchewan, we are 16 percent indigenous, and part of economic reconciliation for me means giving opportunities, not just shadowing opportunities, but you are going to be hired as a director. You are going to be paid union rates, you’re going to get a credit. And although you are emerging, I’m going to hire now a mentor, mostly white men who are not getting jobs right now because they’re all going to BIPOC women, which is fantastic. Just because you want women who are emerging, you want to give them that experience, you also have to support them and make sure they don’t fail. So, I want to do it differently than, you know, on Little Mosque on the Prairie, I was not in charge of the directors. We only had white men directing. And that was a different era. And I feel like the only way we get change is if women are actually the owners of their own shows and can say, “Hey, I want things to be different.” And nobody was questioning me. CBC was like, “Do what you want, here’s the money, you know, as long as you deliver on time and you do your post-production reports, we’re OK.” And so, I wanted to make those changes, and I was able to do that, you know, hiring women, Muslim and indigenous women in the writing rooms, punch up rooms, directing rooms, producing rooms. Like, I got to hire those people and you know, our editor as well as emerging editors making sure they’re in the BIPOC community. The people who make those decisions are the ones who own the production and who own the production company. And that’s where the power lies. And so, I decided the way that you can get those changes is to be that person. And so, I wanted to learn on a web series so that when insha’Allah it goes to half an hour, I can prove to the network I did it for this by myself with help from, you know, various people. But ultimately, I was the person in charge. And then you prove to them, so then they will say, “OK, we’ll let you do the half hour now because you’ve shown us that you could do it.” Otherwise, you get paired with, you know, a company that’s owned by, say white owners who don’t necessarily have the same priorities you do.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Zarqa, you know, one of the things when I look back on your work, the work, the awesome work that’s emerging now, Little Mosque and the and the cultural impact that it had not only in Canada but around the world. I think part of the intentionality behind something like Little Mosque was, in fact, to demystify and break open the possibilities of what being Muslim meant, what being a Muslim in North America, what being Muslim in the modern world meant. And yet, I look at the statistics, I see the reports on Islamophobia, on anti-Muslim prejudice, let alone, you know, the rising incidents of anti-Black racism and anti-Indigenous sentiment and violence. A decade after the show finished, incidents of prejudice have never been higher. Zarqa, what happened? Do we feel that these cultural contributions are making an impact, or are we really up against a really divided world?

ZARQA NAWAZ:

It’s a good question, I’ve been asked that many times, I ask myself that. I mean, the world is becoming more polarized for a variety of reasons that are very complex. You know, we’re not going to get through them in the next 10 minutes. You know, the rich are getting richer, the poor are getting poorer. People are getting more afraid of being able to support their families. And there’s a great deal of fear, a lot of misinformation. You know, social media is fueling much of that. But I think that as creators, we can’t let ourselves be discouraged and say there’s no point. We have that ḥadīth, which says that if you see the end of the world coming and you’re planting a tree, you keep planting your tree. And what it means is you keep going. Because as Muslims, we believe everything is in the hands of our creator and our creator is asking us, “What do you do with the time that you have here?” So, you put on your blinkers and you say, OK, all this is happening, but my job is to keep doing what I’m here to do and do the best job I can and not to feel that my work is not making a contribution. And so, my attitude is, you know, just keep going, do the work. Change is happening. And not become discouraged because, you know, it’s not my job to change the world. My job is to do the best job I can do with whatever resources I have been given in my life ad to do the best that I can do. And God has told us that, you know, this is a world that you will be tested in, with hardship and loss of life and labor, but you seek help through prayer and patience. And so that’s my philosophy is just do the work. Pray. Be patient. Don’t get too scared. We can get scared, but just always go back to the basics. It’s that your intention is to serve your creator in the best way possible and to leave your work in your creator’s hands. And have the best intentions going forward, which is to serve God. And that’s what I do. And I put my blinkers on and go don’t look too much sideways because you’ll get scared.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

And you do so, of course, with a lot of humor and lightness, you know, your work intentionally intersects humor with your faith. And I wonder where does your Muslimness and your sense of humor intersect? What gives us the Zarqa Nawaz touch, brand, feel, sensibility?

ZARQA NAWAZ:

You know, we live in a secular world and things that are religious and things that emanate God consciousness are not really welcome. And I want to break that ceiling, that sort of glass ceiling of faithfulness. And for my book, it was really important that the issues of what does tawakkul mean, what does it mean to trust God? What does it mean to lose one’s faith and regain it through hardship? And what does that mean when Allah says I will test you and you will be tested with hardship and you will deal with it through prayer and patience, and then you will regain, you know, your faith. And in the core, the central theme of the book is how do we regain our trust and faith in God after we go through a really tough time in our lives? And I wanted it to be a universal theme because we all go through it. And it’s kind of human nature that when we go through hardship, we kind of feel God has abandoned us. But when things go well in our lives, we think God loves us [laughs]. And it’s kind of a human nature thing. And I was hoping to write a book about that journey of faith and difficulty of how you ride out the difficulties of life and come back to your faith. And I wanted to write that in such a way that you wouldn’t even notice it until it was over. And to get to the heart of what faith is truly about and make it in a secular world where books about faith and belief in God are not welcome and don’t become New York Times bestsellers. And to make it obvious that that is my mission. And my hope is it becomes a New York Times bestseller and that people–

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Insh’Allah.

ZARQA NAWAZ:

Insh’Allah, and that people understand, you know, I mean, it’s a great story. You know, it tells a lot about Middle Eastern politics and foreign policy in the wars. But at the heart of it, it’s really about how to reestablish or establish your faith in your creator and how to hang in there when things get really rough. And I’m hoping it gives people a sense of comfort and reassurance, and that ultimately is what I’m hoping my comedy is really about is how to help people connect to their faith and to reignite it. And that’s really my only intention in the work that I do, and I try to make sure that’s the underlying message of everything that I create out there and put out into the world.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Zarqa Nawaz, who or what would you like to welcome into your guest house?

ZARQA NAWAZ:

I hope I get a lot of readers who tell me that this book really helped them heal and gave them comfort, you know, they read it at a time of their lives where they really needed strength and a sense of the divine and a sense of reconnection. I wrote it at a difficult time in my life and it helped me reconnect, and it taught me the importance of prayer and connection. And I hope that that is what people get out of this book, that they read it and they, like, Muslim or non-Muslim or nonbelievers, are like, “Wow, like, this is something that really helped me connect to a higher power and helped heal a lot of pain in my life.” That is the guest that I want.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

I think I could see that happening, Zarqa.

ZARQA NAWAZ:

I hope so, Insh’Allah.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

This Being Human is produced by Antica Productions and TVO. Our Senior Producer is Kevin Sexton, with production assistance from Dania Ali. Our Executive Producer is Lisa Gabriele. Mixing and sound design by Phil Wilson. Original music by Boombox Sound. Stuart Coxe is the president of Antica Productions. Katie O’Connor is TVO’s senior producer of podcasts. Laurie Few is the executive for digital at TVO. This Being Human is generously supported by the Aga Khan Museum, one of the world’s leading institutions that explores the artistic, intellectual, and scientific heritage of Islamic civilizations around the world. For more information about the museum go to www.agakhanmuseum.org The Museum wishes to thank Nadir and Shabin Mohamed for their philanthropic support to develop and produce This Being Human.